Arab Gulf, the year that wasn’t: the who, what and why of the Qatar crisis

Novembre/Dicembre 2017 / Monografica

The crisis with Qatar is exerting pressure on the delicate regional balance but may indeed pave the way for an alliance capable of inaugurating a new epic of civil progress and cooperation for the Arab and Muslim world even beyond the Arab Gulf.

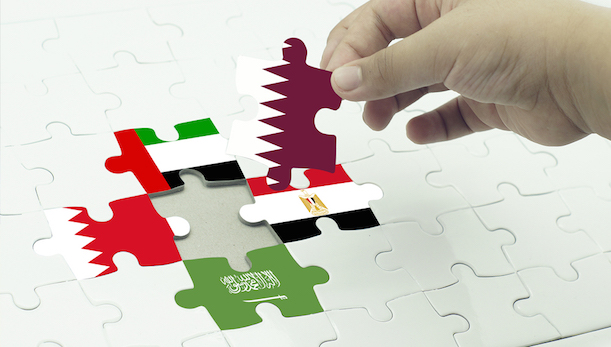

When the history books are written, Ramadan 2017 will be highlighted as marking the beginning of the end of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). On 5 June three members — Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — decided to withdraw their ambassadors, close their airspace and maritime ports and impose a trade boycott on Qatar. Pundits and policy makers chalked-up the unfolding political drama to an intra-regional spat but after six months with no let-up in sight, it’s time to further examine the situation.

In contrast to the avalanche of disinformation flooding cyberspace and trolling the public into believing that Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia somehow triggered the “Qatar Crisis”, it’s time to be honest and admit that it was a long-time coming. The 2017 crisis is directly linked to 2013/2014 when Qatar was also isolated, spurred on by the surfacing of information detailing Doha’s duplicity (at best) and/or active involvement (at worst) into some of the more nefarious chapters of violence in the Arab Gulf—financial assistance to the Houthis in Yemen, coordination with al-Wefaq (a Khomeinst-Shia political-terrorist group supported by Iran via its ideological agent, Ayatollah Isa Qassim) in Bahrain, agitation in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Provinces—all-the-while the al-Jazeera network stands accused of instigation throughout the Gulf and wider Arab world. Doha was working against intra-GCC stability.

Qatar pledged to change. The country’s Emir Shaikh Hamad al-Thani stood down in favour of his son Tamim al-Thani. The GCC turned a page. It was not to last. Doha’s promises did not translate into observable changes and much to the ire of the rest of the bloc its policies began to tear the GCC at the seams. Fast forward to 2017 and Doha’s flirtations with the Muslim Brotherhood and its cosy relations to the al-Nusra Front (a.ka. al-Qaeda in Syria), its deepening strategic cooperation with Iran and Turkey have rendered the Arab Gulf region more vulnerable, less effective in establishing a balance of power and, as a result, more unstable.

This year Kuwait moved to carve out a niche as mediator and after negotiations began, delivered a list of demands for Doha to fulfil in order to end its isolation. These included that Qatar:

1. End ties with Islamist organisations, specifically the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamic State, al-Qaeda Fateh al-Sham and Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

2. Drastically scale-back cooperation with Iran.

3. Close al-Jazeera and other Qatari-supported media.

4. Evict Turkish troops from Qatar’s soil.

These demands are very telling, as is the out-of-hand rejection of them by Qatar. The dynamics of the crisis reflect fundamental differences between Qatar and the rest of the GCC, especially since the most pronounced point of contention is Doha’s ideological vision rooted in the proliferation of political Islam. It has generated a mechanism to provide financial and political assistance to a plethora of groups that pursue Islam as ideology. Doha’s support-the-Muslim-Brotherhood agenda is openly hostile to the agenda pursued by Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, all of whom openly support anti-Islamist factions.

Predictably, Qatar called the demands an affront, an infringement and an attack on Qatar’s sovereignty. It then began deploying strategic tools to cushion itself from political and economic pains. Qatar ate into its sovereign wealth fund and, as reports suggest, has spent some $38 billion (since the crisis began) on projects and public relations events to shore up support in Europe, the US and around the world.

Less predictably however, was Qatar’s about-face in its relations with Turkey and Iran—it went from viewing them through the prism of trade to elevating them to guardians of the state. Iran airlifted food supplies and other primary goods and importantly allowed planes and ships to traverse its territorial waters and airspace. In exchange, Qatar has begun to share its political assets with Iran and has worked to bring European Parliamentarians, business people and other notables on Doha-Tehran working trips. Qatar is helping Iran cold and Iran is rapidly becoming a commodity hub so that Qatar can remain afloat. Yet, Qatar’s Emir will still walk a tightrope in his relations to Iran—most Qataris are loathe to be further alienated from their Arab Gulf brethren and certainly do not want to contribute to increasing Arab-Iranian tensions. The al-Thani Emirs may ultimately be domestically constrained in stitching Qatar to the Islamic Republic.

There are, however, notably fewer constraints in developing Turko-Qatari relations and Turkey’s support has been unconditional. This commitment is, in part, due to Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP Party being affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood (re: Qatar-backed) and in part to Turkish geopolitics—as Ankara seeks entry into the strategic Arab Gulf region. Erdoğan may claim that this crisis is part of a larger conspiracy against political Islam, but it is clear that it is benefiting Turkey immensely. Turkey may not be genuinely interested in solving the Qatar Crisis or a return to the status quo. Turkey’s Parliament has approved the deployment of hundreds of Turkish troops to Doha and they are not in any hurry to head home.

Beyond the region the crisis is forcing a delicate balance. For instance, key Asian actors, such as China and India — dependant on Saudi oil and Qatari gas — have taken a neutral stance in the crisis. They simply do not want to see economic fluctuations. Russia has equally refrained from alienating any of the parties as its assertive Middle East policy has begun to show signs of success and is disinclined to gamble its newfound position by taking sides in this crisis. In Europe, while the EU has officially endorsed Kuwaiti mediation efforts, many Member States follow their foreign policy interests. For instance, France is more sympathetic to Qatar, Germany is following a pragmatic step-by-step policy while the post-Brexit UK is trapped within its very polarised national foreign policy discourse and is further paralysed by indecision at the highest levels. The US is internally divided on this dossier with the White House, Pentagon and State Department jockeying over the most appropriate course of action to follow.

Despite the lacklustre approach from the international community, it is clear that few want to see a transition from crisis to conflict, there is simply too much at stake. Still fewer want to see a drastic reshuffling in the alliances of the region especially since the GCC has stood as a bulwark against the Islamic Republic for nearly 40 years. On this front, however, there may not be much to do. The GCC may never recover from this crisis.

Despite the tensions permeating the Arab Gulf, there may be a silver lining. If the GCC is defunct as a result of the dubious policies of a single member, then perhaps an alliance shake-up is in order. Instead of the Gulf Cooperation Council, it may be time to reach out and develop a wider alliance framework that reinforces the Arab Gulf core by anchoring its periphery. An Arab Cooperation Council (ACC) could be usefully launched to compensate for the fractures left in the GCC by this crisis. Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates could be joined by Egypt and Jordan as the initial alliance but the door would be left open for others — Qatar, Iraq, Yemen — to join once their political systems stabilise to reflect the progressive fundamentals of the new alliance: 1. An alliance of peace and prosperity, 2. An alliance of religious tolerance and diversity, 3. An alliance that roots-out terrorism and radicalism, 4. An alliance of strategic depth to deter shared adversaries and support shared interests, 5. An Arab alliance for the future.

2017 may be remembered as a “year that wasn’t” in the Arab Gulf. With determination, support and a bit of luck, however, 2018 can stand in contrast and become a year in which the Arab Gulf leads the way in civilization-building for the Arab and Muslim worlds. It has the leadership, it has the human capital and the material resources to do so. With the support of the wider international community, the year ahead can leave behind the challenges of the year just passed and the Arab Gulf states are optimistic that the future indeed belongs to cooperation.

INDICE Novembre/dicembre 2017

Editoriale

Monografica

- Golfo Arabo, l’anno che non c’era: cosa, come e perché della crisi del Qatar

- Arabia Saudita, primi importanti passi verso il cambiamento

- Generare forza attraverso l’unità: l’esempio del Bahrein

- Separare la politica dalla religione: un anno di riforme in Bahrein

- Emirati Arabi Uniti, un 2017 in crescita

- Kuwait e Oman, i mediatori del Golfo

- Gulf Economic Visions: come riprogettare l’economia del Golfo

- Arab Gulf, the year that wasn’t: the who, what and why of the Qatar crisis

- Saudi Arabia, the first important step towards change

- Generating strength through unity: the example of Bahrain

- Separating politics from religion: a year of reforms in Bahrain

- United Arab Emirates, a 2017 of growth

- Kuwait and Oman, mediators of the Gulf

- Gulf Economic Visions: how to redesign the Arab Gulf economy